What is downcycling?

Not everything that is reused retains its value. An increasingly relevant concept in sectors like ours – kraft packaging – is downcycling, or cascade recycling.

This is a process whereby a recycled material loses some of its original properties and can therefore no longer be reused to the same standard or for the same purpose.

While this type of recycling is still preferable to discarding waste, it also poses real challenges for companies like ours that are committed to a more circular, efficient and responsible model.

Definition of downcycling

Downcycling refers to the process by which recycled paper or board loses some of its technical properties – such as strength, stiffness or printing quality – and can therefore no longer be reused to make new packaging with the same characteristics.

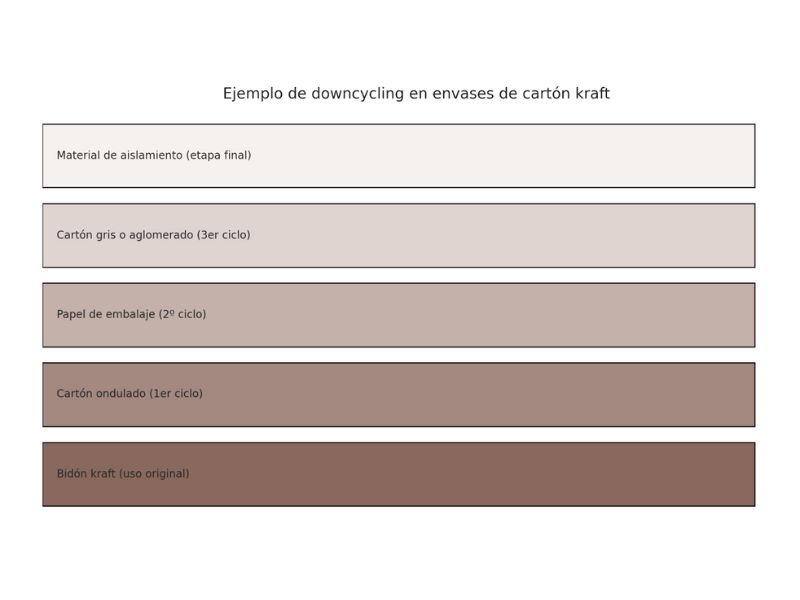

Instead of being turned back into a high-quality kraft drum, the material is used in less demanding products such as bumpers, greyboard, packaging paper or even as part of insulating compounds.

Although this recycling prevents the material from ending up as waste and allows its use to be extended, the cycle is not completely closed, as the material does not return to its original form and does not retain its original functionality. It is an intermediate solution within the circular economy, useful but with limitations.

How does downcycling work?

In simple terms, downcycling occurs when the recycling process degrades the material. In the case of cardboard or paper, for example, the cellulose fibres are shortened with each recovery cycle.

This means that, after several uses, the material loses strength, stiffness or printability. Instead of being able to produce new high-quality packaging, this recycled material is used for less demanding applications such as grey board, packaging protectors or inner tubes for paper rolls.

This phenomenon is not unique to cartonboard: it also occurs with plastics, textiles, metals and even glass, depending on the level of contamination or mixing of materials.

But in the field of kraft paper and board, it is particularly important because it marks the real limit of how many times a package can circulate before it becomes waste.

Is it necessarily a problem?

Not quite. Downcycling makes it possible to extend the useful life of a material and reduce the pressure on natural resources. It is therefore considered a practice that is compatible with the circular economy, although it does not represent the ideal of a closed cycle.

The key is to know at what point the material ceases to be useful for a given use and can have a second (or third) life in other applications.

For example, a heavy-duty kraft drum may have an initial useful life as industrial product packaging. It can then be used as a raw material for producing corrugated board or secondary packaging parts.

Finally, it can end up as low-density recycled paper or even as fuel in controlled processes. At each stage, the value decreases, but the environmental impact is also reduced compared to disposing of the material directly.

What does downcycling mean for us as a manufacturer

As a Kraft packaging manufacturer, understanding downcycling allows us to:

- Design products that are more durable and recyclable from the outset, using mono-material materials, without plastic layers or additives that make recycling difficult.

- Optimise the use of recycled raw materials, knowing in which applications they are most suitable without compromising the quality of the final packaging.

- To inform our customers about the actual recyclability of our products by being transparent about how many life cycles a Kraft packaging can have.

- Participate in circular value chains, collaborating with waste managers, recyclers and other manufacturers to ensure maximum reuse of cartonboard before degradation.

Examples of downcycling applied to Kraft board

Kraft drum → corrugated board

A heavy-duty kraft drum is recycled, but the paper fibres are no longer strong enough to make another drum. They are then used to make corrugated board, used in less structurally demanding boxes.

Kraft cardboard → wrapping paper

After several cycles of use and recycling, the cardboard loses stiffness and print quality. Instead of being discarded, it is transformed into thin kraft paper for wrapping products or as filler material.

Kraft packaging → grey cardboard or chipboard

When the fibres are already too short for demanding technical use, the material is used to manufacture roll inner tubes, industrial separators or binder bases, where aesthetics and strength are secondary.

Mixed cardboard scraps → insulating compound

In the last cycles, when the cardboard is no longer suitable for either structural or packaging use, it can be mixed with other waste and turned into insulation panels or building filler material, without the possibility of being recycled again.

Key differences with other types of recycling

Recycling can be broadly classified into three types:

- Closed recycling: the material retains its quality and can be reincorporated into the original production process.

- Upcycling: the recycled material is transformed into a product of equal or higher added value.

- Downcycling: the material loses quality and is used for less demanding purposes or of lower economic value.

Downcycling is common for materials such as mixed plastics, synthetic textiles, multilayer packaging, industrial compounds or waste with traces of adhesives, inks or pollutants.

Advantages and limitations

Although downcycling is not the ideal solution, it has certain advantages:

- It reduces the volume of waste sent to landfills or incinerators.

- Demand for virgin raw materials decreases.

- It can be applied to materials that are difficult to recycle by other methods.

However, its limitations are obvious:

- It generates products of lower economic value.

- It does not allow materials to be kept in use indefinitely.

- It can convey a false sense of circularity if not communicated properly.

Downcycling is part of today’s recycling reality, especially in sectors with complex or difficult-to-treat materials. Although it does not completely close the cycle, it reduces negative impacts compared to the alternative of non-recycled waste.

However, the real challenge is to move towards solutions that maintain the quality and value of the material over more cycles of use.

To achieve an effective circular economy, companies must focus on eco-design, material innovation and traceability of waste streams.

Recycling alone is not enough if it is not integrated into a broader strategy aimed at preserving the value of resources over time.

You may also be interested in: